|

An Entrepreneur with a Conscience While growing his T-shirt business into a million-dollar company, Rick Roth has refused to abandon his dreams of doing good. By David Whitford I used to call him Baseball Rick. that was back when all I knew about my friend, Rick Roth, were the things anyone noticed right away: He played third base on my softball team (fast-pitch, not a beer league), popped up a lot (swinging for the fences), ran like an old man (he's only forty-two), wore his hair in a ponytail, and drove a rusty blue van with a bumper sticker on it that said "Kill your TV." In time, I learned about another side of Rick. He's a Quaker, a former divinity student, and a dedicated member of Amnesty International, the global human-rights organization. Rick went to his first Amnesty International meeting fourteen years ago, right after his daughter, Hope, was born (the twins, Allison and Christina, arrived two years later). He was a social activist long before he was a father, but Hope's birth galvanized him, he says; made him feel that much more proprietary towards the world his children would inherit. His involvement quickly grew. In the early 1990's as coordinator of Amnesty International Group 133 in Somerville, Massachusetts, Rick led a campaign that raised $30,000 and won political asylum for the family of Jose Sotz, a Guatemalan trade unionist. Sotz had been the victim of an assassination attempt that left his three-year-old son, also Jose, a paraplegic. |

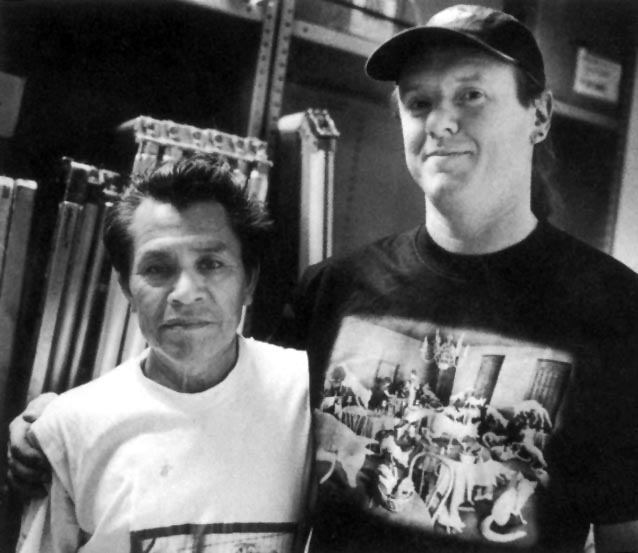

"While there is on a T-shirt worn by Rick Roth |

|

All along, I was vaguly aware that Rick also had a T-shirt business. I guess I thought maybe he was silk-screening in his basement and peddling his wares on the sidewalk. In fact, that's exactly how Rick started his business six years ago. Today, his company, Mirror Image, occupies 10,000 suare feet in a shop near Central Square in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and employs thirty people. Revenues in 1995 topped $2.6 million. Lately, I've been trying to make sense of the different parts of Rick's life: the entrepreneur and the social activist. I don't think it's as simple for him as the common divide between vocation and avocation. Rick seems to care as much about running his business ("I would feel like a failure if Mirror Image went bankrupt") as he does about helping make the world a better place; he's passionate in both arenas, and moves easily between them. If you ask Rick, he'll tell you that being an entrepreneur is something he's had to "adapt my nature to." Maybe, but I'm not sure I believe him. I think Rick's probably an entrepreneur in his bones. Not a typical entrepreneur, certainly, but a classic entrepreneur nonetheless. That's what makes Rick's life such an interesting case study-and Rick, himself, a role model. He's an entrepreneur whose skill and natural inclination as a company-builder are sources of (not just complements to) his effectiveness as a social activist. The first thing I had to learn about entrepreneurs when I started writing for Inc. magazine is that not all of them are in it for the money. Some are, of course, and they tend to attract the most attention. Among those I've met, John Streep of The Furst Group, a long-distance reseller that topped the 1995 Inc. 500 list of the fastest growing private companies in America, comes to mind. Streep's skill, his passion, is spotting an opportunity (any opportunity, he's not choosy) and capitalizing on it. He describes the exhilaration he and his partner felt, launching their new business, this way: "It wasn't a question of whether we were going to get 'em. It was, 'What color will our Lear jets be?'" Streep is an opportunist. That's one kind of entrepreneur. Joe Mansueto, CEO of Morningstar, a mutual-fund rating company that's made the Inc. 500 list four times, is so unlike Streep it's hard to imagine the two of them standing in the same room. Mansueto is more of a loner than an opportunist. He spent much of his early twenties trying on various careers. When he couldn't find the one that fit him perfectly, he created it. His values are those of his favorite thinker, Henry Thoreau: simplicity, indepenence, thrift. For Mansueto, Morningstar is less about making himself rich than it is about pursuing his own interests, surrounding himself with like-minded companions, and "controlling my own time." That's another kind on entrepreneur. Then there's Harry Clark, CEO of MuniFinancial services, another Inc. 500 company. He seems to crave dominion not just over his own life, as does Mansueto, but also over the lives of others. He goes in for gimmicks like chartering a bus to the local shopping mall at Christmastime, handing out ordering them to spend it all on themselves. "What I can do for the people who work for me is change their lives," he says, sounding disturbingly like a nineteenth-century factory-owner. "Spiritually, intellectually, economically, politically." Clark is a controller. What kind of entrepreneur is Rick? Clearly, it's not the money that drives him. His salary is $30,000-less than that of several of his own employees. Now that's a little misleading. Rick has built something of value in Mirror Image and the equity is all his; the day will come when Rick will want to think about ways of converting some of that value into cash-"After seven years of working seventy hours a week, I'm owed a little bit of money." On the other hand, a small-business owner whose sole focus is the bottom line probably doesn't pay 100 percent of his employees' health insurance costs, as Rick does. He certainly doesn't prod them into becoming a union shop (the impetus was all Rick's); or turn down a lucrative order for 30,000 T-shirts because the job called for a photo of Rush Limbough on the front and a list of ten reasons not to vote for Bill Clinton on the back. Clearly, Rick's no opportunist. Nor is he a loner, exactly, though it's hard to imagine where he would fit in professionally if he didn't own his own business. He once went a decade (the 1970's) between haircuts. He has a thing against collars (he wears T-shirts wherever he goes--even, once, to a meeting with Governer Weld of Massachusetts on behalf of Amnesty International). Like Mansueto, Rick bounced around for a whild before finding his place. He grew up as part of a working class family in Connecticut. His dad was a bank manager, but he was the white-collar exception; the rest of the extended family, Rick says, were "truck drivers, welders, and criminals." |

Jose Sotz and Rick Roth |

At Colgate College, Rick majored in philosophy and religion, and went on to enroll in Harvard Divinity School. His life as a divinity student was the opposite of cloistered. He got himself arrested during a demonstration at the Seabrook nuclear power plant, and spent two weeks in jail. Between classes, he counseled recovering heroin addicts in a methadone clinic run by the City of Boston. Because he enjoyed the counseling, and because his goal all along had been to become a social worker (rather than a minister or a teacher), he dropped out of divinity school after one year and went to work full-time in the methadone clinic. That lasted three years, untill the program, faced with funding cutbacks, stopped doing counseling. Afterwards, with a couple of partners, he started a remodeling company, and was happy for a while. Construction was a welcome antidote to the frustrations of social work-"Whether you help someone or not is nebulous. Whether you build a wall or not is concrete." Then in 1983, he came down with a rare joint disease called pigmented villonodular synovitis, which destroyed the cartilage in his right ankle and left him unable to walk (much less run the bases) without pain. With physical labor no longer on option, he began printing T-shirts in his basement. |

|

In Mirror Image, Rick has created his own version of an ideal community-a diverse group of artists and artisans who worry more about the quality of their work than meeting sales goals, and who share a commitment to social justice. Like Mansueto's Morningstar, Rick's community is the opposite of insular; it's active, in play; a collective force for change, not a sanctuary. While he was still a carpenter, Rick's social-justice work was something he did on the side, when he wasn't working. These days, the lines have blurred. "I try to use all the resources of the business to help Amnesty." Rick says. "Sometimes it distracts, but a lot of the time it's just part of what I do." Evidence of that intermingling is all over the plant, beginning with the diverse collection of window stickers on display by the front door: "Cambridge Chamber of Commerce;" "Screenprinting and Graphic Imaging Association International;" and "Amnesty International." Jose Sotz, settled now with his family in Cambridge, works in Mirror Image's screen department. "I really didn't want him to work for me at first," says Rick. "He's a person I look up to and respect. To be his boss didn't appeal to me." But Sotz needed a job, and Rick could offer him one, close enough to home that Sotz can take care of his son when he needs to. Finally, many of Rick's customers know about his commitment to Amnesty International and support him with more than just their business. Rhino Records, for instance, recently donated $600 for modems to help Amnesty International volunteers monitor human rights abuses via the internet. The benefits flow both ways. About a year ago, Rick heard of a group of students at Broad Meadows High School in Quincy, Massachusetts, who were trying to collect money for a good cause. They wanted to build a school in Pakistan to honor child-labor activist Iqbal Masih, who was murdered on Easter Sunday 1995, when he was twelve years old (Hope, May/June 1996). Rick, and several Mirror Image artists, visited Broad Meadows, and loaned equiptment and design expertise to help the students build a web site celebrating Masih's life and soliciting donations. In the year that followed, two things happened: More than $100,000 in donations poured in from all over the world, allowing work on the school to begin; and Rick began hearing from people and organizations who wanted Mirror Image to design web sites for them. A charitable act led to a new source of revenue for the company. If the only skills Rick brought to his work as a social activist were management know-how and an understanding of the difference between gross revenues and profit, he would still be a rare and valuable contributor. But Rick brings much more than that. He brings his peculiar sensibility as an entrepreneur. That's his special power, and his gift. Being an entrepreneur has nothing to do, ultimately, with being on opportunist, or a loner, or a controlling person; those are seconday traits. An entrepreneur is someone who takes nothing for granted, assumes change is possible, and follows through; someone incapable of confronting reality without thinking about ways to improve it; and for whom action is a natural consequence of thought. Every genuine entrepreneur is that way. It's the source of all their strength. Some just misapply it, that's all. They could learn from Rick. |

All material designed and copyrighted by

Questions or problems to report about this web site? Contact the Webmaster at webmaster@mirrorimage.com